The Ultimate Guide to Sail Types and Rigs (with Pictures)

What's that sail for? Generally, I don't know. So I've come up with a system. I'll explain you everything there is to know about sails and rigs in this article.

What are the different types of sails? Most sailboats have one mainsail and one headsail. Typically, the mainsail is a fore-and-aft bermuda rig (triangular shaped). A jib or genoa is used for the headsail. Most sailors use additional sails for different conditions: the spinnaker (a common downwind sail), gennaker, code zero (for upwind use), and stormsail.

Each sail has its own use. Want to go downwind fast? Use a spinnaker. But you can't just raise any sail and go for it. It's important to understand when (and how) to use each sail. Your rigging also impacts what sails you can use.

On this page:

Different sail types, the sail plan of a bermuda sloop, mainsail designs, headsail options, specialty sails, complete overview of sail uses, mast configurations and rig types.

This article is part 1 of my series on sails and rig types. Part 2 is all about the different types of rigging. If you want to learn to identify every boat you see quickly, make sure to read it. It really explains the different sail plans and types of rigging clearly.

Guide to Understanding Sail Rig Types (with Pictures)

First I'll give you a quick and dirty overview of sails in this list below. Then, I'll walk you through the details of each sail type, and the sail plan, which is the godfather of sail type selection so to speak.

Click here if you just want to scroll through a bunch of pictures .

Here's a list of different models of sails: (Don't worry if you don't yet understand some of the words, I'll explain all of them in a bit)

- Jib - triangular staysail

- Genoa - large jib that overlaps the mainsail

- Spinnaker - large balloon-shaped downwind sail for light airs

- Gennaker - crossover between a Genoa and Spinnaker

- Code Zero or Screecher - upwind spinnaker

- Drifter or reacher - a large, powerful, hanked on genoa, but made from lightweight fabric

- Windseeker - tall, narrow, high-clewed, and lightweight jib

- Trysail - smaller front-and-aft mainsail for heavy weather

- Storm jib - small jib for heavy weather

I have a big table below that explains the sail types and uses in detail .

I know, I know ... this list is kind of messy, so to understand each sail, let's place them in a system.

The first important distinction between sail types is the placement . The mainsail is placed aft of the mast, which simply means behind. The headsail is in front of the mast.

Generally, we have three sorts of sails on our boat:

- Mainsail: The large sail behind the mast which is attached to the mast and boom

- Headsail: The small sail in front of the mast, attached to the mast and forestay (ie. jib or genoa)

- Specialty sails: Any special utility sails, like spinnakers - large, balloon-shaped sails for downwind use

The second important distinction we need to make is the functionality . Specialty sails (just a name I came up with) each have different functionalities and are used for very specific conditions. So they're not always up, but most sailors carry one or more of these sails.

They are mostly attached in front of the headsail, or used as a headsail replacement.

The specialty sails can be divided into three different categories:

- downwind sails - like a spinnaker

- light air or reacher sails - like a code zero

- storm sails

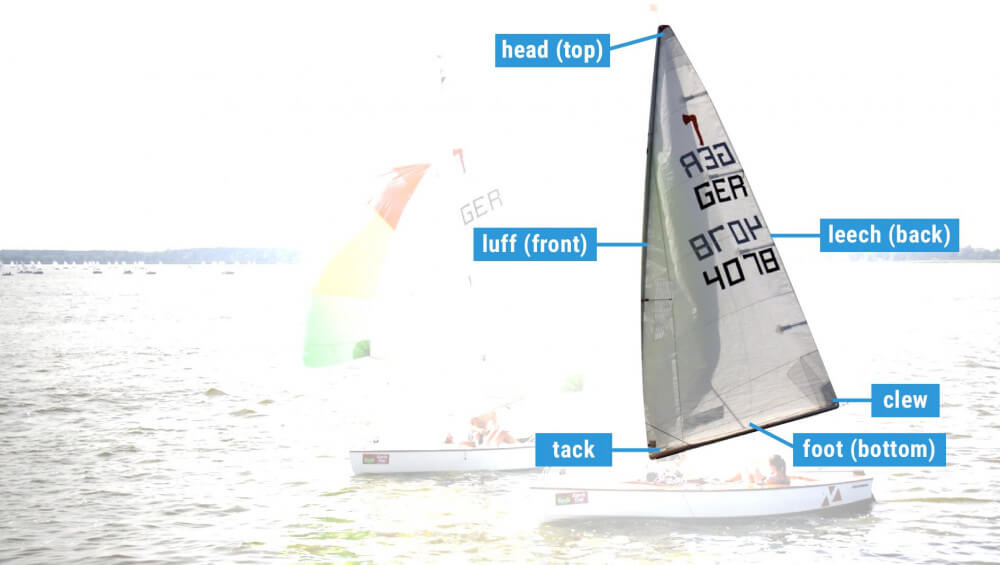

The parts of any sail

Whether large or small, each sail consists roughly of the same elements. For clarity's sake I've took an image of a sail from the world wide webs and added the different part names to it:

- Head: Top of the sail

- Tack: Lower front corner of the sail

- Foot: Bottom of the sail

- Luff: Forward edge of the sail

- Leech: Back edge of the sail

- Clew: Bottom back corner of the sail

So now we speak the same language, let's dive into the real nitty gritty.

Basic sail shapes

Roughly speaking, there are actually just two sail shapes, so that's easy enough. You get to choose from:

- square rigged sails

- fore-and-aft rigged sails

I would definitely recommend fore-and-aft rigged sails. Square shaped sails are pretty outdated. The fore-and-aft rig offers unbeatable maneuverability, so that's what most sailing yachts use nowadays.

Square sails were used on Viking longships and are good at sailing downwind. They run from side to side. However, they're pretty useless upwind.

A fore-and-aft sail runs from the front of the mast to the stern. Fore-and-aft literally means 'in front and behind'. Boats with fore-and-aft rigged sails are better at sailing upwind and maneuvering in general. This type of sail was first used on Arabic boats.

As a beginner sailor I confuse the type of sail with rigging all the time. But I should cut myself some slack, because the rigging and sails on a boat are very closely related. They are all part of the sail plan .

A sail plan is made up of:

- Mast configuration - refers to the number of masts and where they are placed

- Sail type - refers to the sail shape and functionality

- Rig type - refers to the way these sails are set up on your boat

There are dozens of sails and hundreds of possible configurations (or sail plans).

For example, depending on your mast configuration, you can have extra headsails (which then are called staysails).

The shape of the sails depends on the rigging, so they overlap a bit. To keep it simple I'll first go over the different sail types based on the most common rig. I'll go over the other rig types later in the article.

Bermuda Sloop: the most common rig

Most modern small and mid-sized sailboats have a Bermuda sloop configuration . The sloop is one-masted and has two sails, which are front-and-aft rigged. This type of rig is also called a Marconi Rig. The Bermuda rig uses a triangular sail, with just one side of the sail attached to the mast.

The mainsail is in use most of the time. It can be reefed down, making it smaller depending on the wind conditions. It can be reefed down completely, which is more common in heavy weather. (If you didn't know already: reefing is skipper terms for rolling or folding down a sail.)

In very strong winds (above 30 knots), most sailors only use the headsail or switch to a trysail.

The headsail powers your bow, the mainsail powers your stern (rear). By having two sails, you can steer by using only your sails (in theory - it requires experience). In any case, two sails gives you better handling than one, but is still easy to operate.

Let's get to the actual sails. The mainsail is attached behind the mast and to the boom, running to the stern. There are multiple designs, but they actually don't differ that much. So the following list is a bit boring. Feel free to skip it or quickly glance over it.

- Square Top racing mainsail - has a high performance profile thanks to the square top, optional reef points

- Racing mainsail - made for speed, optional reef points

- Cruising mainsail - low-maintenance, easy to use, made to last. Generally have one or multiple reef points.

- Full-Batten Cruising mainsail - cruising mainsail with better shape control. Eliminates flogging. Full-length battens means the sail is reinforced over the entire length. Generally have one or multiple reef points.

- High Roach mainsail - crossover between square top racing and cruising mainsail, used mostly on cats and multihulls. Generally have one or multiple reef points.

- Mast Furling mainsail - sails specially made to roll up inside the mast - very convenient but less control; of sail shape. Have no reef points

- Boom Furling mainsail - sails specially made to roll up inside the boom. Have no reef points.

The headsail is the front sail in a front-and-aft rig. The sail is fixed on a stay (rope, wire or rod) which runs forward to the deck or bowsprit. It's almost always triangular (Dutch fishermen are known to use rectangular headsail). A triangular headsail is also called a jib .

Headsails can be attached in two ways:

- using roller furlings - the sail rolls around the headstay

- hank on - fixed attachment

Types of jibs:

Typically a sloop carries a regular jib as its headsail. It can also use a genoa.

- A jib is a triangular staysail set in front of the mast. It's the same size as the fore-triangle.

- A genoa is a large jib that overlaps the mainsail.

What's the purpose of a jib sail? A jib is used to improve handling and to increase sail area on a sailboat. This helps to increase speed. The jib gives control over the bow (front) of the ship, making it easier to maneuver the ship. The mainsail gives control over the stern of the ship. The jib is the headsail (frontsail) on a front-and-aft rig.

The size of the jib is generally indicated by a number - J1, 2, 3, and so on. The number tells us the attachment point. The order of attachment points may differ per sailmaker, so sometimes J1 is the largest jib (on the longest stay) and sometimes it's the smallest (on the shortest stay). Typically the J1 jib is the largest - and the J3 jib the smallest.

Most jibs are roller furling jibs: this means they are attached to a stay and can be reefed down single-handedly. If you have a roller furling you can reef down the jib to all three positions and don't need to carry different sizes.

Originally called the 'overlapping jib', the leech of the genoa extends aft of the mast. This increases speed in light and moderate winds. A genoa is larger than the total size of the fore-triangle. How large exactly is indicated by a percentage.

- A number 1 genoa is typically 155% (it used to be 180%)

- A number 2 genoa is typically 125-140%

Genoas are typically made from 1.5US/oz polyester spinnaker cloth, or very light laminate.

This is where it gets pretty interesting. You can use all kinds of sails to increase speed, handling, and performance for different weather conditions.

Some rules of thumb:

- Large sails are typically good for downwind use, small sails are good for upwind use.

- Large sails are good for weak winds (light air), small sails are good for strong winds (storms).

Downwind sails

Thanks to the front-and-aft rig sailboats are easier to maneuver, but they catch less wind as well. Downwind sails are used to offset this by using a large sail surface, pulling a sailboat downwind. They can be hanked on when needed and are typically balloon shaped.

Here are the most common downwind sails:

- Big gennaker

- Small gennaker

A free-flying sail that fills up with air, giving it a balloon shape. Spinnakers are generally colorful, which is why they look like kites. This downwind sail has the largest sail area, and it's capable of moving a boat with very light wind. They are amazing to use on trade wind routes, where they can help you make quick progress.

Spinnakers require special rigging. You need a special pole and track on your mast. You attach the sail at three points: in the mast head using a halyard, on a pole, and on a sheet.

The spinnaker is symmetrical, meaning the luff is as long as its leech. It's designed for broad reaching.

Gennaker or cruising spinnaker

The Gennaker is a cross between the genoa and the spinnaker. It has less downwind performance than the spinnaker. It is a bit smaller, making it slower, but also easier to handle - while it remains very capable. The cruising spinnaker is designed for broad reaching.

The gennaker is a smaller, asymmetric spinnaker that's doesn't require a pole or track on the mast. Like the spinnaker, and unlike the genoa, the gennaker is set flying. Asymmetric means its luff is longer than its leech.

You can get big and small gennakers (roughly 75% and 50% the size of a true spinnaker).

Also called ...

- the cruising spinnaker

- cruising chute

- pole-less spinnaker

- SpinDrifter

... it's all the same sail.

Light air sails

There's a bit of overlap between the downwind sails and light air sails. Downwind sails can be used as light air sails, but not all light air sails can be used downwind.

Here are the most common light air sails:

- Spinnaker and gennaker

Drifter reacher

Code zero reacher.

A drifter (also called a reacher) is a lightweight, larger genoa for use in light winds. It's roughly 150-170% the size of a genoa. It's made from very lightweight laminated spinnaker fabric (1.5US/oz).

Thanks to the extra sail area the sail offers better downwind performance than a genoa. It's generally made from lightweight nylon. Thanks to it's genoa characteristics the sail is easier to use than a cruising spinnaker.

The code zero reacher is officially a type of spinnaker, but it looks a lot like a large genoa. And that's exactly what it is: a hybrid cross between the genoa and the asymmetrical spinnaker (gennaker). The code zero however is designed for close reaching, making it much flatter than the spinnaker. It's about twice the size of a non-overlapping jib.

A windseeker is a small, free-flying staysail for super light air. It's tall and thin. It's freestanding, so it's not attached to the headstay. The tack attaches to a deck pad-eye. Use your spinnakers' halyard to raise it and tension the luff.

It's made from nylon or polyester spinnaker cloth (0.75 to 1.5US/oz).

It's designed to guide light air onto the lee side of the main sail, ensuring a more even, smooth flow of air.

Stormsails are stronger than regular sails, and are designed to handle winds of over 45 knots. You carry them to spare the mainsail. Sails

A storm jib is a small triangular staysail for use in heavy weather. If you participate in offshore racing you need a mandatory orange storm jib. It's part of ISAF's requirements.

A trysail is a storm replacement for the mainsail. It's small, triangular, and it uses a permanently attached pennant. This allows it to be set above the gooseneck. It's recommended to have a separate track on your mast for it - you don't want to fiddle around when you actually really need it to be raised ... now.

| Sail | Type | Shape | Wind speed | Size | Wind angle |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bermuda | mainsail | triangular, high sail | < 30 kts | ||

| Jib | headsail | small triangular foresail | < 45 kts | 100% of foretriangle | |

| Genoa | headsail | jib that overlaps mainsail | < 30 kts | 125-155% of foretriangle | |

| Spinnaker | downwind | free-flying, balloon shape | 1-15 kts | 200% or more of mainsail | 90°–180° |

| Gennaker | downwind | free-flying, balloon shape | 1-20 kts | 85% of spinnaker | 75°-165° |

| Code Zero or screecher | light air & upwind | tight luffed, upwind spinnaker | 1-16 kts | 70-75% of spinnaker | |

| Storm Trysail | mainsail | small triangular mainsail replacement | > 45 kts | 17.5% of mainsail | |

| Drifter reacher | light air | large, light-weight genoa | 1-15 kts | 150-170% of genoa | 30°-90° |

| Windseeker | light air | free-flying staysail | 0-6 kts | 85-100% of foretriangle | |

| Storm jib | strong wind headsail | low triangular staysail | > 45 kts | < 65% height foretriangle |

Why Use Different Sails At All?

You could just get the largest furling genoa and use it on all positions. So why would you actually use different types of sails?

The main answer to that is efficiency . Some situations require other characteristics.

Having a deeply reefed genoa isn't as efficient as having a small J3. The reef creates too much draft in the sail, which increases heeling. A reefed down mainsail in strong winds also increases heeling. So having dedicated (storm) sails is probably a good thing, especially if you're planning more demanding passages or crossings.

But it's not just strong winds, but also light winds that can cause problems. Heavy sails will just flap around like laundry in very light air. So you need more lightweight fabrics to get you moving.

What Are Sails Made Of?

The most used materials for sails nowadays are:

- Dacron - woven polyester

- woven nylon

- laminated fabrics - increasingly popular

Sails used to be made of linen. As you can imagine, this is terrible material on open seas. Sails were rotting due to UV and saltwater. In the 19th century linen was replaced by cotton.

It was only in the 20th century that sails were made from synthetic fibers, which were much stronger and durable. Up until the 1980s most sails were made from Dacron. Nowadays, laminates using yellow aramids, Black Technora, carbon fiber and Spectra yarns are more and more used.

Laminates are as strong as Dacron, but a lot lighter - which matters with sails weighing up to 100 kg (220 pounds).

By the way: we think that Viking sails were made from wool and leather, which is quite impressive if you ask me.

In this section of the article I give you a quick and dirty summary of different sail plans or rig types which will help you to identify boats quickly. But if you want to really understand it clearly, I really recommend you read part 2 of this series, which is all about different rig types.

You can't simply count the number of masts to identify rig type But you can identify any rig type if you know what to look for. We've created an entire system for recognizing rig types. Let us walk you through it. Read all about sail rig types

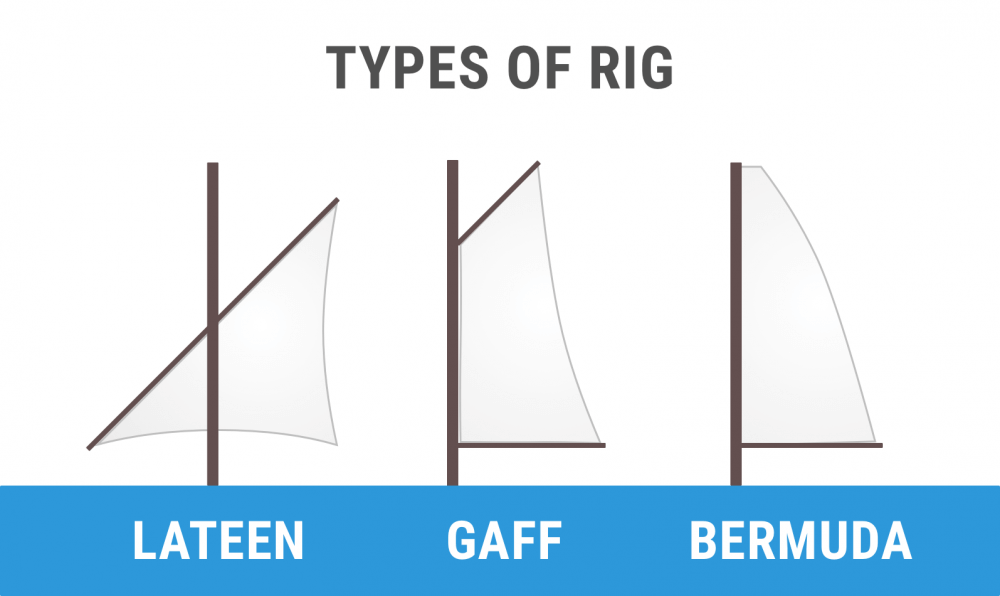

As I've said earlier, there are two major rig types: square rigged and fore-and-aft. We can divide the fore-and-aft rigs into three groups:

- Bermuda rig (we have talked about this one the whole time) - has a three-sided mainsail

- Gaff rig - has a four-sided mainsail, the head of the mainsail is guided by a gaff

- Lateen rig - has a three-sided mainsail on a long yard

There are roughly four types of boats:

- one masted boats - sloop, cutter

- two masted boats - ketch, schooner, brig

- three masted - barque

- fully rigged or ship rigged - tall ship

Everything with four masts is called a (tall) ship. I think it's outside the scope of this article, but I have written a comprehensive guide to rigging. I'll leave the three and four-masted rigs for now. If you want to know more, I encourage you to read part 2 of this series.

One-masted rigs

Boats with one mast can have either one sail, two sails, or three or more sails.

The 3 most common one-masted rigs are:

- Cat - one mast, one sail

- Sloop - one mast, two sails

- Cutter - one mast, three or more sails

1. Gaff Cat

2. Gaff Sloop

Two-masted rigs

Two-masted boats can have an extra mast in front or behind the main mast. Behind (aft of) the main mast is called a mizzen mast . In front of the main mast is called a foremast .

The 5 most common two-masted rigs are:

- Lugger - two masts (mizzen), with lugsail (cross between gaff rig and lateen rig) on both masts

- Yawl - two masts (mizzen), fore-and-aft rigged on both masts. Main mast much taller than mizzen. Mizzen without mainsail.

- Ketch - two masts (mizzen), fore-and-aft rigged on both masts. Main mast with only slightly smaller mizzen. Mizzen has mainsail.

- Schooner - two masts (foremast), generally gaff rig on both masts. Main mast with only slightly smaller foremast. Sometimes build with three masts, up to seven in the age of sail.

- Brig - two masts (foremast), partially square-rigged. Main mast carries small lateen rigged sail.

4. Schooner

5. Brigantine

This article is part 1 of a series about sails and rig types If you want to read on and learn to identify any sail plans and rig type, we've found a series of questions that will help you do that quickly. Read all about recognizing rig types

Related Questions

What is the difference between a gennaker & spinnaker? Typically, a gennaker is smaller than a spinnaker. Unlike a spinnaker, a gennaker isn't symmetric. It's asymmetric like a genoa. It is however rigged like a spinnaker; it's not attached to the forestay (like a jib or a genoa). It's a downwind sail, and a cross between the genoa and the spinnaker (hence the name).

What is a Yankee sail? A Yankee sail is a jib with a high-cut clew of about 3' above the boom. A higher-clewed jib is good for reaching and is better in high waves, preventing the waves crash into the jibs foot. Yankee jibs are mostly used on traditional sailboats.

How much does a sail weigh? Sails weigh anywhere between 4.5-155 lbs (2-70 kg). The reason is that weight goes up exponentially with size. Small boats carry smaller sails (100 sq. ft.) made from thinner cloth (3.5 oz). Large racing yachts can carry sails of up to 400 sq. ft., made from heavy fabric (14 oz), totaling at 155 lbs (70 kg).

What's the difference between a headsail and a staysail? The headsail is the most forward of the staysails. A boat can only have one headsail, but it can have multiple staysails. Every staysail is attached to a forward running stay. However, not every staysail is located at the bow. A stay can run from the mizzen mast to the main mast as well.

What is a mizzenmast? A mizzenmast is the mast aft of the main mast (behind; at the stern) in a two or three-masted sailing rig. The mizzenmast is shorter than the main mast. It may carry a mainsail, for example with a ketch or lugger. It sometimes doesn't carry a mainsail, for example with a yawl, allowing it to be much shorter.

Special thanks to the following people for letting me use their quality photos: Bill Abbott - True Spinnaker with pole - CC BY-SA 2.0 lotsemann - Volvo Ocean Race Alvimedica and the Code Zero versus SCA and the J1 - CC BY-SA 2.0 Lisa Bat - US Naval Academy Trysail and Storm Jib dry fit - CC BY-SA 2.0 Mike Powell - White gaff cat - CC BY-SA 2.0 Anne Burgess - Lugger The Reaper at Scottish Traditional Boat Festival

Hi, I stumbled upon your page and couldn’t help but notice some mistakes in your description of spinnakers and gennakers. First of all, in the main photo on top of this page the small yacht is sailing a spinnaker, not a gennaker. If you look closely you can see the spinnaker pole standing on the mast, visible between the main and headsail. Further down, the discription of the picture with the two German dinghies is incorrect. They are sailing spinnakers, on a spinnaker pole. In the farthest boat, you can see a small piece of the pole. If needed I can give you the details on the difference between gennakers and spinnakers correctly?

Hi Shawn, I am living in Utrecht I have an old gulf 32 and I am sailing in merkmeer I find your articles very helpful Thanks

Thank you for helping me under stand all the sails there names and what there functions were and how to use them. I am planning to build a trimaran 30’ what would be the best sails to have I plan to be coastal sailing with it. Thank you

Hey Comrade!

Well done with your master piece blogging. Just a small feedback. “The jib gives control over the bow of the ship, making it easier to maneuver the ship. The mainsail gives control over the stern of the ship.” Can you please first tell the different part of a sail boat earlier and then talk about bow and stern later in the paragraph. A reader has no clue on the newly introduced terms. It helps to keep laser focused and not forget main concepts.

Shawn, I am currently reading How to sail around the World” by Hal Roth. Yes, I want to sail around the world. His book is truly grounded in real world experience but like a lot of very knowledgable people discussing their area of expertise, Hal uses a lot of terms that I probably should have known but didn’t, until now. I am now off to read your second article. Thank You for this very enlightening article on Sail types and their uses.

Shawn Buckles

HI CVB, that’s a cool plan. Thanks, I really love to hear that. I’m happy that it was helpful to you and I hope you are of to a great start for your new adventure!

Hi GOWTHAM, thanks for the tip, I sometimes forget I haven’t specified the new term. I’ve added it to the article.

Nice article and video; however, you’re mixing up the spinnaker and the gennaker.

A started out with a question. What distinguishes a brig from a schooner? Which in turn led to follow-up questions: I know there are Bermuda rigs and Latin rig, are there more? Which in turn led to further questions, and further, and further… This site answers them all. Wonderful work. Thank you.

Great post and video! One thing was I was surprised how little you mentioned the Ketch here and not at all in the video or chart, and your sample image is a large ship with many sails. Some may think Ketch’s are uncommon, old fashioned or only for large boats. Actually Ketch’s are quite common for cruisers and live-aboards, especially since they often result in a center cockpit layout which makes for a very nice aft stateroom inside. These are almost exclusively the boats we are looking at, so I was surprised you glossed over them.

Love the article and am finding it quite informative.

While I know it may seem obvious to 99% of your readers, I wish you had defined the terms “upwind” and “downwind.” I’m in the 1% that isn’t sure which one means “with the wind” (or in the direction the wind is blowing) and which one means “against the wind” (or opposite to the way the wind is blowing.)

paul adriaan kleimeer

like in all fields of syntax and terminology the terms are colouual meaning local and then spead as the technology spread so an history lesson gives a floral bouque its colour and in the case of notical terms span culture and history adds an detail that bring reverence to the study simply more memorable.

Hi, I have a small yacht sail which was left in my lock-up over 30 years ago I basically know nothing about sails and wondered if you could spread any light as to the make and use of said sail. Someone said it was probably originally from a Wayfayer wooden yacht but wasn’t sure. Any info would be must appreciated and indeed if would be of any use to your followers? I can provide pics but don’t see how to include them at present

kind regards

Leave a comment

You may also like, 17 sailboat types explained: how to recognize them.

Ever wondered what type of sailboat you're looking at? Identifying sailboats isn't hard, you just have to know what to look for. In this article, I'll help you.

How Much Sailboats Cost On Average (380+ Prices Compared)

Sail Rigs And Types - The Only Guide You Need

A well-designed sailboat is a thing of pure beauty. Whether you're a proud owner of one, a guest on one, or a shore-side admirer, you'll fall in love with the gliding sails, the excitement of a race, and the eco-friendly nature of these sophisticated yet magnificent vessels. With good sails, great design, and regular maintenance, sails and rigs are an important part of a sailboat.

If you’re thinking about going sailing, one of the first things you have to understand is the variety of modern sail plans. Unlike old sailboats, modern sailboats don't need huge, overlapping headsails and multiple masts just to get moving. In the past, when sailboats were heavy, keels were long, the only way to get the boat moving was with a massive relative sail area. You needed as much square footage as you could just to get your sailboat moving. But with the invention of fiberglass hulls, aluminum or composite masts, high-tensile but low diameter lines and stats, and more efficient sails, sailboats no longer need to plan for such large sail plans.. Still, there are various rig styles, from the common sloop, to the comfortable cat-rig, to the dual masted ketch and schooner, there are various sail types and rigs to choose from. The most important thing is to know the different types of sails and rigs and how they can make your sailing even more enjoyable.

There are different types of sails and rigs. Most sailboats have one mainsail and one headsail. The mainsail is generally fore-and-aft rigged and is triangular shaped. Various conditions and courses require adjustments to the sails on the boats, and, other than the mainsail, most boats can switch out their secondary sail depending on various conditions.. Do you want to sail upwind or go downwind? You cannot hoist just any sail and use it. It's, therefore, of great importance to understand how and when to use each sail type.

In this in-depth article, we'll look at various sail types and rigs, and how to use them to make your sailing more enjoyable.

Table of contents

Different Sail Types

It is perhaps worth noting that a sailboat is only as good as its sails. The very heart of sailing comes in capturing the wind using artfully trimmed sails and turning that into motion. . Ask any good sailor and he'll tell you that knowing how and when to trim the sails efficiently will not only improve the overall performance of your boat but will elevate your sailing experience. In short, sails are the driving force of sailboats.

As such, it's only natural that you should know the different types of sails and how they work. Let's first highlight different sail types before going into the details.

- Jib - triangular staysail

- Spinnaker - huge balloon-shaped downwind sail for light airs

- Genoa - huge jib that overlaps the mainsail

- Gennaker - a combination of a spinnaker and genoa

- Code zero - reaching genoa for light air

- Windseeker - tall, narrow, high-clewed, and lightweight jib

- Drifter - versatile light air genoa made from particularly lightweight cloth

- Storm jib - a smaller jib meant for stormy conditions

- Trysail - This is a smaller front-and-aft sail for heavy weather

The mainsail is the principal sail on a boat. It's generally set aft of the mainmast. Working together with the jib, the mainsail is designed to create the lift that drives the sailboat windward. That being said, the mainsail is a very powerful component that must always be kept under control.

As the largest sail, and the geometric center of effort on the boat, the mainsail is tasked with capturing the bulk of the wind that's required to propel the sailboat. The foot, the term for the bottom of any sail, secures to the boom, which allows you to trim the sail to your heading. The luff, the leading edge of the sail, is attached to the mast. An idealized mainsail would be able to swing through trim range of 180°, the full semi-circle aft of the mast, though in reality, most larger boats don’t support this full range of motion, as a fully eased sail can occasionally be unstable in heavy breeze.

. As fully controlling the shape of the mainsail is crucial to sailing performance, there are many different basic mainsail configurations. For instance, you can get a full-batten mainsail, a regular mainsail with short battens, or a two-plus-two mainsail with two full-length battens. Hyper-high performance boats have even begun experimenting with winged sails which are essentially trimmable airplane wings! Moreover, there are numerous sail controls that change the shape by pulling at different points on the sail, boom, or mast. Reefing, for instance, allows you to shorten the sail vertically, reducing the amount of sail area when the boat is overpowered.

Features of a Mainsail

Several features will affect how a particular sail works and performs. Some features will, of course, affect the cost of the sail while others may affect its longevity. All in all, it's essential to decide the type of mainsail that's right for you and your sailing application.

Sail Battens, the Roach, and the Leech

The most difficult part of the sail to control, but also the most important, are the areas we refer to as the leech and the roach. The roach is the part of the sail that extends backwards past the shortest line between the clew, at the end of the boom, and the top of the mast. It makes up roughly the back third of the sail. The leech is the trailing edge of the sail, the backmost curve of the roach. Together, these two components control the flow of the air off the back of the sail, which greatly affects the overall sail performance. If the air stalls off the backside of the sail, you will find a great loss in performance. Many sail controls, including the boom vang, backstay, main halyard, and even the cunningham, to name a few, focus on keeping this curve perfect.

As for parts of the sail itself, battens control the overall horizontal shape of the sail. Battens are typically made from fiberglass or wood and are built into batten pockets. They're meant to offer support and tension to maintain the sail shape Depending on the sail technology you want to use, you may find that full battens, which extend from luff to leech, or short battens, just on the trailing edge, are the way to go. Fully battened sails tend to be more expensive, but also higher performance.

Fully Battened Mainsails

They're generally popular on racing multihulls as they give you a nice solid sail shape which is crucial at high speeds. In cruising sailboats , fully battened mainsails have a few benefits such as:

- They prevent the mainsail from ragging. This extends the life of the sail, and makes maneuvers and trimming easier for the crew.

- It provides shape and lift in light-air conditions where short-battened mainsails would collapse.

On the other hand, fully-battened mainsails are often heavier, made out of thicker material, and can chafe against the standing rigging with more force when sailing off the wind.

Short Battens

On the other hand, you can choose a mainsail design that relies mostly on short battens, towards the leech of the sail. This tends to work for lighter cloth sails, as the breeze, the headsail, and the rigging help to shape the sail simply by the tension of the rig and the flow of the wind. The battens on the leech help to preserve the shape of the sail in the crucial area where the air is flowing off the back of the sail, keeping you from stalling out the entire rig.

The only potential downside is that these short battens deal with a little bit of chafe and tension in their pockets, and the sail cloth around these areas ought to be reinforced. If your sails do not have sufficient reinforcement here, or you run into any issues related to batten chafe, a good sail maker should be able to help you extend the life of your sails for much less than the price of a new set.

How to Hoist the Mainsail

Here's how to hoist the mainsail, assuming that it relies on a slab reefing system and lazy jacks and doesn't have an in-mast or in-boom furling system.

- Maintain enough speed for steeragewhile heading up into the wind

- Slacken the mainsheet, boom vang, and cunningham

- Make sure that the lazy jacks do not catch the ends on the battens by pulling the lazy jacks forward.

- Ensure that the reefing runs are free to run and the proper reefs are set if necessary.

- Raise the halyard as far as you can depending on pre-set reefs.

- Tension the halyard to a point where a crease begins to form along the front edge

- Re-set the lazy jacks

- Trim the mainsail properly while heading off to your desired course

So what's Right for You?

Your mainsail will depend on how you like sailing your boat and what you expect in terms of convenience and performance. That being said, first consult the options that the boatbuilder or sailmakers suggest for your rig. When choosing among the various options, consider what you want from the sail, how you like to sail, and how much you're willing to spend on the mainsail.

The headsail is principally the front sail in a fore-and-aft rig. They're commonly triangular and are attached to or serve as the boat’s forestay. They include a jib and a genoa.

A jib is a triangular sail that is set ahead of the foremost sail. For large boats, the roto-furling jib has become a common and convenient way to rig and store the jib. Often working in shifts with spinnakers, jibs are the main type of headsails on modern sailboats. Jibs take advantage of Bournoulli’s Principle to break the incoming breeze for the mainsail, greatly increasing the speed and point of any boat. By breaking the incoming wind and channeling it through what we call the ‘slot,’ the horizontal gap between the leech of the jib and the luff of the mainsail, the jib drastically increases the efficiency of your mainsail. It additionally balances the helm on your rudder by pulling the bow down, as the mainsail tends to pull the stern down. .

The main aim of the jib is to increase the sail area for a given mast size. It improves the aerodynamics of the mainsails so that your sailboat can catch more wind and thereby sail faster, especially in light air

Using Jibs on Modern Sailboats

In the modern contexts, jib’s mainly serve increase the performance and overall stability of the mainsail. The jib can also reduce the turbulence of the mainsail on the leeward side.

On Traditional Vessels

Traditional vessels such as schooners have about three jibs. The topmast carried a jib topsail, the main foresail is called the jib, while the innermost jib is known as the staysail. The first two were employed almost exclusively by clipper ships.

How to Rig the Jibs

There are three basic ways to rig the jib.

Track Sheets - A relatively modern approach to the self-tacking jib, this entails placing all the trimming hardware on a sliding track forward of the mast. This means that on each tack, the hardware slides from one side of the boat to the other. This alleviates the need to switch sheets and preserves the trim angle on both sides, though it can be finnicky and introduce friction.

Sheet up the Mast - This is a very popular approach and for a good reason. Hoist the jib sheet up the mast high enough to ensure that there's the right tension through the tack. Whether internally or externally, the sheet returnsto the deck and then back to the cockpit just like the rest of the mast baselines. The fact the hardware doesn't move through the tacks is essential in reducing friction.

Sheet Forward - This method revolves around ensuring that the jib sheet stays under constant pressure so that it does not move through the blocks in the tacks. This is possible if the through-deck block is extremely close to the jib tack. Your only challenge will only be to return the sheet to the cockpit. This is, however, quite challenging and can cause significant friction.

Dual Sheeting - The traditional method, especially on smaller dinghies, though it is not self-tacking. This requires a two ended or two separate sheet system, where one sheet runs to a block on starboard, and the other to port. Whenever you tack or gybe, this means you have to switch which sheet is active and which is slack, which is ok for well crewed boats, but a potential issue on under-crewed boats.

Another important headsail, a genoa is essentially a large jib that usually overlaps the mainsail or extends past the mast, especially when viewed from the other side. In the past, a genoa was known as the overlapping jib and is technically used on twin-mast boats and single-mast sloops such as ketches and yawls. A genoa has a large surface area, which is integral in increasing the speed of the vessel both in moderate and light winds.

Genoas are generally characterized by the percentage they cover. In most cases, sail racing classes stipulate the limit of a genoa size. In other words, genoas are usually classified by coverage.

Top-quality genoa trim is of great importance, especially if the wind is forward of the beam. This is because the wind will first pass over the genoa before the mainsail. As such, a wrongly sheeted genoa can erroneously direct the wind over the mainsail,spelling doom to your sailing escapades. While you can perfectly adjust the shape of a genoa using the mast rake, halyard tension, sheet tension, genoa car positioning, and backstay tension, furling and unfurling a genoa can be very challenging, especially in higher winds.

That being said, here are the crucial steps to always keep in mind.

- Unload and ease the loaded genoa sheet by going to a broad reach

- Do not use the winch; just pull on the furling line

- Keep a very small amount of pressure or tension on the loaded genoa sheet

- Secure the furling line and tighten the genoa sheets

- Get on the proper point of sail

- Have the crew help you and release the lazy genoa sheets

- Maintain a small tension while easing out the furling line

- Pull-on a loaded genoa sheet

- Close or cleat off the rope clutch when the genoa is unfurled

- Trim the genoa

To this end, it's important to note that genoas are popular in some racing classes. This is because they only categorize genoas based on the fore-triangle area covered, which essentially allows a genoa to significantly increase the actual sail area. On the contrary, keep in mind that tacking a genoa is quite a bit harder than a jib, as the overlapping area can get tangled with the mast and shrouds. It's, therefore, important to make sure that the genoa is carefully tended, particularly when tacking.

Downwind Sails

Modern sailboats are a lot easier to maneuver thanks to the fore-and-aft rig. Unfortunately, when sailing downwind they catch less wind, and downwind sails are a great way of reducing this problem. They include the spinnaker and the gennaker.

A spinnaker will, without a doubt, increase your sailing enjoyment. But why are they often buried in the cabin of cruising boats? Well, the first few attempts to rig and set a spinnaker can be difficult without enough help and guidance. Provided a solid background, however, spinnakers are quite straightforward and easy to use and handle with teamwork and enough practice. More importantly, spinnakers can bring a light wind passage to life and can save your engine.

Spinnakers are purposely designed for sailing off the wind; they fill with wind and balloon out in front of your sailboat. Structured with a lightweight fabric such as nylon, the spinnaker is also known as a kite or chute, as they look like parachutes both in structure and appearance.

A perfectly designed spinnaker should have taut leading edges when filled. This mitigates the risk of lifting and collapsing. A spinnaker should have a smooth curve when filled and devoid of depressions and bubbles that might be caused by the inconsistent stretching of the fabric. The idea here is that anything other than a smooth curve may reduce the lift and thereby reduce performance.

Types of Spinnakers

There are two main types of spinnakers: symmetric spinnakers and asymmetric spinnakers.

Asymmetric Spinnakers

Flown from a spinnaker pole or bowsprit fitted to the bow of the boat, asymmetric spinnakers resemble large jibs and have been around since the 19th century. The concept of asymmetric spinnaker revolves around attaching the tack of the spinnaker at the bow and pulling it around during a gybe.

Asymmetric spinnakers have two sheets just like a jib., These sheets are attached at the clew and never interact directly with the spinnaker pole. This is because the other corner of the spinnaker is fixed to the bowsprit. The asymmetric spinnaker works when you pull in one sheet while releasing the other. This makes it a lot easier to gybe but is less suited to sailing directly downwind. There is the loophole of having the asymmetric spinnaker gybed to the side opposite of the boom, so that the boat is sailing ‘wing-on-wing,’ though this is a more advanced maneuver, generally reserved for certain conditions and tactical racing situations.

On the contrary, the asymmetric spinnaker is perfect for fast planing dinghies. This is because such vessels have speeds that generate apparent wind forward. Because asymmetrics, by nature, prefer to sail shallower downwind angles, this apparent wind at high speeds makes the boat think that it is sailing higher than it really is, allowing you to drive a little lower off the breeze than normal. . In essence, the asymmetric spinnaker is vital if you're looking for easy handling.

Symmetric Spinnakers

Symmetric spinnakers are a classic sail type that has been used for centuries for controlling boats by lines known as a guy and a sheet. The guy, which is a windward line, is attached to the tack of the sail and stabilized by a spinnaker pole. The sheet, which is the leeward line, is attached to the clew of the spinnaker and is essential in controlling the shape of the spinnaker sail.

When set correctly, the leading edges of the symmetric spinnaker should be almost parallel to the wind. This is to ensure that the airflow over the leading edge remains attached. Generally, the spinnaker pole should be at the right angles to the apparent wind and requires a lot of care when packing.

The main disadvantage of this rig is the need to gybe the spinnaker pole whenever you gybe the boat. This is a complicated maneuver, and is one of the most common places for spinnakers to rip or get twisted. If, however, you can master this maneuver, you can sail at almost any angle downwind!

How to Use Spinnaker Effectively

If you decide to include the spinnakers to your sailboat, the sailmaker will want to know the type of boat you have, what kind of sailing you do, and where you sail. As such, the spinnaker that you end up with should be an excellent and all-round sail and should perform effectively off the breeze

The type of boat and where you'll be sailing will hugely influence the weight of your spinnaker cloth. In most cases, cruising spinnakers should be very light, so if you've decided to buy a spinnaker, make sure that it's designed per the type of your sailboat and where you will be sailing. Again, you can choose to go for something lighter and easier to set if you'll be sailing alone or with kids who are too young to help.

Setting up Spinnakers

One of the main reasons why sailors distrust spinnakers is because they don't know how to set them up. That being said, a perfectly working spinnaker starts with how you set it up and this revolves around how you carefully pack it and properly hook it up. You can do this by running the luff tapes and ensuring that the sails are not twisted when packed into the bag. If you are using large spinnakers, the best thing to do is make sure that they're set in stops to prevent the spinnakers from filling up with air before you even hoist them fully.

But even with that, you cannot fully set the spinnaker while sailing upwind. Make sure to bear away and have your pole ready to go as you turn downwind. You should then bear away to a reach before hoisting. Just don't hoist the spinnakers from the bow as this can move the weight of the crew and equipment forward.

Used when sailing downwind, a gennaker is asymmetric sail somewhere between a genoa and a spinnaker. It sets itself apart because it gennaker is a free-flying asymmetric spinnaker but it is tacked to the bowsprit like the jib.

Let's put it into perspective. Even though the genoa is a great sail for racing and cruising, sailors realized that it was too small to be used in a race or for downwind sail and this is the main reason why the spinnaker was invented. While the spinnakers are large sails that can be used for downwind sail, they are quite difficult to handle especially if you're sailing shorthanded. As such, this is how a gennaker came to be: it gives you the best of both worlds.

Gennakers are stable and easy to fly and will add to your enjoyment and downwind performance.

The Shape of a Gennaker

As we've just noted, the gennaker is asymmetrical. It doesn't attach to the forestay like the genoa but has a permanent fitting from the mast to bow. It is rigged exactly like a spinnaker but its tack is fastened to the bowsprit. This is fundamentally an essential sail if you're looking for something to bridge the gap between a genoa and a spinnaker.

Setting a Gennaker

When cruising, the gennaker is set with the tack line from the bow, a halyard, and a sheet that's led to the aft quarter. Attach the tack to a furling unit and attach it to a fitting on the hull near the very front of the sailboat. You can then attach the halyard that will help in pulling it up to the top of the mast before attaching it to the clew. The halyard can then run back to the winches to make the controlling of the sail shape easier, just like when using the genoa sail.

In essence, a gennaker is a superb sail that will give you the maximum versatility of achieving the best of both a genoa and a spinnaker, especially when sailing downwind. This is particularly of great importance if you're cruising by autopilot or at night.

Light Air Sails

Even though downwind sails can be used as light air sails, not all light air sails can be used for downwind sailing. In other words, there's a level of difference between downwind sails and light air sails. Light air sails include code zero, windseeker, and drifter reacher.

A cross between an asymmetrical spinnaker and a genoa, a code zero is a highly modern sail type that's generally used when sailing close to the wind in light air. Although the initial idea of code zero was to make a larger genoa, it settled on a narrow and flat spinnaker while upholding the shape of a genoa.

Modern boats come with code zero sails that can be used as soon as the sailboat bears off close-hauled even a little bit. It has a nearly straight luff and is designed to be very flat for close reaching. This sail is designed to give your boat extra performance in light winds, especially in boats that do not have overlapping genoas. It also mitigates the problem of loss of power when you are reaching with a non-overlapping headsail. Really, it is closer to a light air jib that sacrifices a little angle for speed.

In many conditions, a code zero sail can go as high as a sailboat with just a jib. By hoisting a code zero, you'll initially have to foot off about 15 degrees to fill it and get the power that you require to heel and move the boat. The boat will not only speed up but will also allow you to put the bow up while also doing the same course as before you set the zero. In essence, code zero can be an efficient way of giving your boat about 30% more speed and this is exactly why it's a vital inventory item in racing sailboats.

When it comes to furling code zero, the best way to do it is through a top-down furling system as this will ensure that you never get a twist in the system.

Generally used when a full size and heavier sail doesn't stay stable or pressurized, a windseeker is a very light sail that's designed for drifting conditions. This is exactly why they're designed with a forgiving cloth to allow them to handle these challenging conditions.

The windseeker should be tacked at the headstay with two sheets on the clew. To help this sail fill in the doldrums, you can heel the boat to whatever the apparent leeward side is and let gravity help you maintain a good sail shape while reaching.The ideal angle of a windseeker should be about 60 degrees.

Though only used in very specific conditions, the windseeker is so good at this one job that it is worth the investment if you plan on a long cruise. Still, you can substitute most off the breeze sails for this in a pinch, with slightly less performance gain, likely with more sacrifices in angle to the breeze.

Drifter Reacher

Many cruising sailors often get intimidated by the idea of setting and trimming a drifter if it's attached to the rig at only three corners or if it's free-flying. But whether or not a drifter is appropriate for your boat will hugely depend on your boat's rig, as well as other specific details such as your crew's ability to furl and unfurl the drifter and, of course, your intended cruising grounds.

But even with that, the drifter remains a time-honored sail that's handy and very versatile. Unlike other light air sails, the drifter perfectly carries on all points of sails as it allows the boat to sail close-hauled and to tack. It is also very easy to control when it's set and struck. In simpler terms, a drifter is principally a genoa that's built of lightweight fabric such as nylon. Regardless of the material, the drifter is a superb sail if you want to sail off a lee shore without using the genoa.

Generally stronger than other regular sails, stormsails are designed to handle winds of over 45 knots and are great when sailing in stormy conditions. They include a storm jib and a trysail.

If you sail long and far enough, chances are you have or will soon be caught in stormy conditions. Under such conditions, storm jibs can be your insurance and you'll be better off if you have a storm jib that has the following features:

- Robustly constructed using heavyweight sailcloth

- Sized suitably for the boat

- Highly visible even in grey and white seas

That's not all; you should never go out there without a storm jib as this, together with the trysail, is the only sails that will be capable of weathering some of nature's most testing situations.

Storm jibs typically have high clews to give you the flexibility of sheet location. You can raise the sail with a spare halyard until its lead position is closed-hauled in the right position. In essence, storm jib is your insurance policy when out there sailing: you should always have it but always hope that you never have to use it.

Also known as a spencer, a trysail is a small, bright orange, veritably bullet-proof, and triangular sail that's designed to save the boat's mainsail from winds over 45 knots and works in the same way as a storm jib. It is designed to enable you to make progress to windward even in strong and stormy winds.

Trysails generally use the same mast track as the mainsail but you have to introduce the slides into the gate from the head of the trysail.

There are two main types of rigs: the fore-and-aft rig and the square rigg.

Fore-and-aft Rig

This is a sailing rig that chiefly has the sails set along the lines of the keel and not perpendicular to it. It can be divided into three categories: Bermuda rig, Gaff rig, and Lateen rig.

Bermuda Rig - Also known as a Marconi rig, this is the typical configuration of most modern sailboats. It has been used since the 17th century and remains one of the most efficient types of rigs. The rig revolves around setting a triangular sail aft of the mast with the head raised to the top of the mast. The luff should run down the mast and be attached to the entire length.

Gaff Rig - This is the most popular fore-and-aft rig on vessels such as the schooner and barquentine. It revolves around having the sail four-cornered and controlled at its peak. In other words, the head of the mainsail is guided by a gaff.

Lateen Rig - This is a triangular fore-and-aft rig whereby a triangular sail is configured on a long yard that's mounted at a given angle of the mast while running in a fore-and-aft direction. Lateen rig is commonly used in the Indian Ocean and the Mediterranean.

Square Rigged

This is a rig whereby the mainsails are arranged in a horizontal spar so that they're square or vertical to the mast and the keel of the boat. The square rig is highly efficient when sailing downwind and was once very popular with ocean-going sailboats.

Unquestionably, sailing is always pleasurable. Imagine turning off the engine of your boat, hoisting the sails, and filling them with air! This is, without a doubt, a priceless moment that will make your boat keel and jump forward!

But being propelled by the noiseless motion of the wind and against the mighty currents and pounding waves of the seas require that you know various sail types and how to use them not just in propelling your boat but also in ensuring that you enjoy sailing and stay safe. Sails are a gorgeous way of getting forward. They remain the main fascination of sailboats and sea cruising. If anything, sails and boats are inseparable and are your true friends when out there on the water. As such, getting to know different types of sails and how to use them properly is of great importance.

All in all, let's wish you calm seas, fine winds, and a sturdy mast!

Related Articles

Daniel Wade

I've personally had thousands of questions about sailing and sailboats over the years. As I learn and experience sailing, and the community, I share the answers that work and make sense to me, here on Life of Sailing.

by this author

Learn About Sailboats

Sailboat Parts

Most Recent

Dufour Sailboats Guide & Common Problems

October 16, 2024

What Does "Sailing By The Lee" Mean?

October 3, 2023

Important Legal Info

Lifeofsailing.com is a participant in the Amazon Services LLC Associates Program, an affiliate advertising program designed to provide a means for sites to earn advertising fees by advertising and linking to Amazon. This site also participates in other affiliate programs and is compensated for referring traffic and business to these companies.

Similar Posts

The Best Sailing Schools And Programs: Reviews & Ratings

September 26, 2023

Affordable Sailboats You Can Build at Home

September 24, 2024

Best Small Sailboat Ornaments

September 12, 2023

Popular Posts

Best Liveaboard Catamaran Sailboats

December 28, 2023

Can a Novice Sail Around the World?

Elizabeth O'Malley

June 15, 2022

4 Best Electric Outboard Motors

How Long Did It Take The Vikings To Sail To England?

10 Best Sailboat Brands (And Why)

December 20, 2023

7 Best Places To Liveaboard A Sailboat

Guide to Understanding Sail Rig Types

Sailing is a timeless pursuit that connects us to nature while offering a sense of freedom on the water. But if you’re new to sailing, one of the first things that might confuse you is the vast array of different sail rigs. The term “rig” refers to the configuration of the sails, masts, and rigging that make up a boat’s sail plan. Understanding the different types of sail rigs is crucial for anyone interested in sailing, whether you’re a seasoned sailor or just starting your journey.

In this guide, we’ll break down the most common types of sail rigs, explain their features, and help you understand how each rig impacts sailing performance. We’ll also include pictures to give you a clearer understanding of what each rig looks like in action.

What is a Sail Rig?

A sail rig is the framework of a sailing vessel that supports the sails and allows them to catch the wind to propel the boat. It consists of the mast (vertical support), boom (horizontal support), sails, and rigging (ropes and cables). Sail rigs are classified according to how the sails are positioned and how they are controlled. The most common rigs are:

- Windmill rigs (Wind turbines)

Each rig type has its advantages, disadvantages, and ideal conditions, which are influenced by the boat’s design and its intended purpose. Let’s explore each of these rigs in detail.

1. Sloop Rig

The sloop is one of the most common and popular sail rigs, especially for smaller recreational sailboats. It features a single mast and a fore-and-aft sail plan, which means that the sails run along the length of the boat rather than perpendicular to the hull. A typical sloop has a main sail and a headsail , which could be a jib or genoa .

Key Characteristics:

- One mast : The sloop uses a single mast located near the middle of the boat.

- Two primary sails : The main sail and the headsail.

- Simple and efficient : The sloop rig is easy to handle, especially for solo sailors.

Advantages:

- Fast and maneuverable : The sloop rig is known for its excellent upwind performance and ease of handling.

- Versatile : The rig can be used in a wide range of conditions, making it ideal for cruising and racing.

- Cruising, day sailing, and racing on smaller to mid-sized boats.

2. Cutter Rig

The cutter rig is similar to the sloop but has an additional foresail, creating a more complex sail plan. The cutter features a main sail , a jib , and a staysail (a third sail positioned between the mast and the headsail). The cutter rig has been favored by sailors who need a more balanced sail plan and improved downwind performance.

- Three sails : A main sail, jib, and staysail.

- Multiple headsails : The cutter has more flexibility when changing sails in different wind conditions.

- Balanced : The additional headsail helps balance the boat under various conditions.

- More control : It’s easier to adjust sails for different wind strengths, making it well-suited for long-distance cruising.

- Offshore cruising and boats designed for heavier weather conditions.

3. Ketch Rig

A ketch rig features two masts: a main mast and a mizzen mast (a smaller mast located aft or towards the back of the boat). The ketch rig is often found on cruising boats and offers increased sail area with better balance and more control.

- Two masts : The main mast and a smaller mizzen mast.

- Multiple sails : The ketch rig typically has a main sail, mizzen sail, and a foresail.

- Better balance : The mizzen sail provides additional balance, especially in heavier winds.

- Reduced heeling : The ketch rig can be easier to handle in heavy weather due to its balanced sail plan.

- Multiple sail options : You can adjust the sails to match different wind conditions for increased comfort and efficiency.

- Long-distance cruising, especially in changing wind conditions or heavy weather.

4. Yawl Rig

The yawl is similar to the ketch, with two masts, but the mizzen mast is positioned even further aft—often closer to the rudder. This setup gives the yawl rig a more balanced and less “weather-helm” feel (the tendency of a boat to steer itself to windward).

- Two masts : Main mast and a smaller mizzen mast aft of the rudder.

- More aft mizzen mast : The mizzen is typically much smaller than the main sail and does not contribute much to the boat’s speed, but rather its balance.

- Increased maneuverability : The yawl rig’s smaller mizzen can be used to assist with steering, making it easier to maneuver in tight spaces.

- Balanced sail plan : Offers stability and control, especially when the boat is under the wind.

- Smaller cruising boats, especially in more confined or tricky sailing conditions.

5. Catboat Rig

The catboat rig features a single mast with a large, single sail attached to the mast. This rig is very simple and was historically favored by fishermen for its ease of use. Its distinctive feature is the lack of a headsail—everything is controlled from the single main sail.

- Single mast, single sail : The boat has one large sail and no jib or staysail.

- High mast placement : The mast is often placed far forward, sometimes near the bow.

- Simplicity : The single-sail system makes it easy to operate, perfect for beginners or solo sailors.

- Stability : The large sail gives the boat a lot of power without the complexity of additional sails.

- Smaller, easy-to-sail boats, especially for day sailing in calm waters.

6. Square Rig

Square rigs are more complex and are typically used on tall ships and large sailing vessels. In this rig, the sails are positioned perpendicular to the mast, making them look like giant squares or rectangles when viewed from above. This rig requires more crew and is often used in trade or adventure sailing.

- Square sails : Sails are mounted at right angles to the mast.

- Multiple masts : Often used on ships with three or more masts, each equipped with square sails.

- Powerful downwind performance : Square rigs are excellent at sailing with the wind behind them (downwind).

- Large sail area : These rigs can capture large amounts of wind, making them suitable for large ocean-going vessels.

- Tall ships, commercial vessels, and historical replicas.

7. Windmill Rigs

Windmill rigs are a type of wind-powered sail designed to capture the wind more efficiently. These rigs are typically not used for traditional sailing but for generating power. They are increasingly used in eco-friendly or renewable energy initiatives.

- Vertical wind turbines : Instead of using traditional sails, these rigs incorporate vertical-axis wind turbines.

- Renewable energy generation : They convert wind energy into electricity rather than using it for propulsion.

- Sustainable power : Windmill rigs help harness wind for renewable energy on boats and ships.

- Low-maintenance : Windmill rigs are typically low-maintenance compared to traditional sails.

- Eco-friendly boats and ships that need renewable energy sources.

Understanding the various sail rig types is essential for anyone looking to explore the world of sailing. Each rig has its unique advantages and is suited for specific types of sailing—whether it’s for speed, comfort, or handling adverse conditions. From the simple and efficient sloop to the powerful and historic square rig, the choice of rig greatly influences the sailing experience.

Whether you’re learning to sail or considering purchasing a sailboat, knowing the characteristics and uses of different rig types will help you make informed decisions about your sailing journey. Happy sailing!

Happy Boating!

Share Fast-Track Owning a Boat • Resource Center with your friends and leave a comment below with your thoughts.

Read Fast-Track Your Sailing Dream until we meet in the next article.

Leave a Comment Cancel reply

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

Jordan Yacht Brokerage

We Never Underestimate Your Dreams

Sailboat rig types: sloop, cutter, ketch, yawl, schooner, cat.

Naval architects designate sailboat rig types by number and location of masts. The six designations are sloop, cutter, cat, ketch, yawl, and schooner. Although in defining and describing these six rigs I may use terminology associated with the sail plan, the rig type has nothing to do with the number of sails, their arrangement or location. Such terms that have no bearing on the rig type include headsail names such as jib, genoa, yankee; furling systems such as in-mast or in-boom; and sail parts such as foot, clew, tack, leach, and roach. Rig questions are one of the primary areas of interest among newcomers to sailing and studying the benefits of each type is a good way to learn about sailing. I will deal with the rigs from most popular to least.

Sloop The simplest and most popular rig today is the sloop. A sloop is defined as a yacht whose mast is somewhere between stations 3 and 4 in the 10 station model of a yacht. This definition places the mast with two thirds of the vessel aft and one third forward. The sloop is dominant on small and medium sized yachts and with the shift from large foretriangles (J-dimension in design parlance) to larger mains a solid majority on larger yachts as well. Simple sloop rigs with a single headsail point the highest because of the tighter maximum sheeting angle and therefore have the best windward performance of the rig types. They are the choice for one-design racing fleets and America’s cup challenges. The forestay can attached either at the masthead or some fraction below. These two types of sloops are described respectively as masthead or fractionally rigged. Fractionally rigged sloops where the forestay attaches below the top of the mast allow racers to easily control head and main sail shapes by tightening up the backstay and bending the mast.

Cutter A cutter has one mast like the sloop, and people rightfully confuse the two. A cutter is defined as a yachts whose mast is aft of station 4. Ascertaining whether the mast is aft or forward of station 4 (what if it is at station 4?) is difficult unless you have the design specifications. And even a mast located forward of station 4 with a long bowsprit may be more reasonably referred to as a cutter. The true different is the size of the foretriangle. As such while it might annoy Bob Perry and Jeff_h, most people just give up and call sloops with jibstays cutters. This arrangement is best for reaching or when heavy weather dictates a reefed main. In moderate or light air sailing, forget the inner staysail; it will just backwind the jib and reduce your pointing height.

Ketch The ketch rig is our first that has two masts. The main is usually stepped in location of a sloop rig, and some manufactures have used the same deck mold for both rig types. The mizzen, as the slightly shorter and further aft spar is called, makes the resulting sail plan incredibly flexible. A ketch rig comes into her own on reaching or downwind courses. In heavy weather owners love to sail under jib and jigger (jib and mizzen). Upwind the ketch suffers from backwinding of the mizzen by the main. You can add additional headsails to make a cutter-ketch.

Yawl The yawl is similar to the ketch rig and has the same trade-offs with respect to upwind and downwind performance. She features two masts just like on a ketch with the mizzen having less air draft and being further aft. In contrast and much like with the sloop vs. cutter definition, the yawl mizzen’s has much smaller sail plan. During the CCA era, naval architects defined yawl as having the mast forward or aft of the rudderpost, but in today’s world of hull shapes (much like with the sloop/cutter) that definition does not work. The true different is the height of the mizzen in proportion to the main mast. The yawl arrangement is a lovely, classic look that is rarely if ever seen on modern production yachts.

Schooner The schooner while totally unpractical has a romantic charm. Such a yacht features two masts of which the foremost is shorter than the mizzen (opposite of a ketch rig). This change has wide affects on performance and sail plan flexibility. The two masts provide a base to fly unusual canvas such as a mule (a triangular sail which spans between the two spars filling the space aft of the foremast’s mainsail). The helm is tricky to balance because apparent wind difference between the sails, and there is considerable backwinding upwind. Downwind you can put up quite a bit of canvas and build up speed.

Cat The cat rig is a single spar design like the sloop and cutter, but the mast location is definately forward of station 3 and maybe even station. You see this rig on small racing dinghies, lasers and the like. It is the simplest of rigs with no headsails and sometimes without even a boom but has little versatility. Freedom and Nonesuch yachts are famous for this rig type. A cat ketch variation with a mizzen mast is an underused rig which provides the sailplan flexibility a single masted cat boat lacks. These are great fun to sail.

Conclusion Sloop, cutter, ketch, yawl, schooner, and cat are the six rig types seen on yachts. The former three are widely more common than the latter three. Each one has unique strengths and weaknesses. The sloop is the best performing upwind while the cat is the simplest form. Getting to know the look and feel of these rig types will help you determine kind of sailing you enjoy most.

5 Replies to “Sailboat Rig Types: Sloop, Cutter, Ketch, Yawl, Schooner, Cat”

Thanks for this information. I’m doing my research on what type of sailboat I will eventually buy and was confused as to all the different configurations! This helped quite a bit.

- Pingback: ketch or schooner - Page 2 - SailNet Community

- Pingback: US Coast Guard Auxiliary Courses – Always Ready! | Escape Artist Chronicles

Being from the south, my distinction between a ketch and a yawl: if that mizzen falls over on a ketch, the boat will catch it; if it falls over on a yawl, it’s bye bye y’all.

I thought a Yawl had to have the mizzen mast behind the rudder and a ketch had the mizzen forward of the rudder.

Leave a Reply

Your email address will not be published. Required fields are marked *

Save my name, email, and website in this browser for the next time I comment.

IMAGES

COMMENTS

Sep 17, 2023 · The rig consists of the sail and mast hardware. The sail rig and sail type are both part of the sail plan. We usually use the sail rig type to refer to the type of boat. Let's start by taking a look at the most commonly used modern sail rigs. Don't worry if you don't exactly understand what's going on. At the end of this article, you'll ...

The principal types include: A square-rig mainsail is a square sail attached at the bottom of the main mast. A Bermuda-rig mainsail is a triangular sail with the luff attached to the mast with the foot or lower edge generally attached to a boom. A gaff-rig mainsail is a quadrilateral sail whose head is supported by a gaff.

Sail type - refers to the sail shape and functionality; Rig type - refers to the way these sails are set up on your boat; There are dozens of sails and hundreds of possible configurations (or sail plans). For example, depending on your mast configuration, you can have extra headsails (which then are called staysails).

Jun 15, 2022 · Bermuda Rig - Also known as a Marconi rig, this is the typical configuration of most modern sailboats. It has been used since the 17th century and remains one of the most efficient types of rigs. It has been used since the 17th century and remains one of the most efficient types of rigs.

Nov 6, 2024 · The term “rig” refers to the configuration of the sails, masts, and rigging that make up a boat’s sail plan. Understanding the different types of sail rigs is crucial for anyone interested in sailing, whether you’re a seasoned sailor or just starting your journey. In this guide, we’ll break down the most common types of sail rigs ...

Jan 13, 2011 · Naval architects designate sailboat rig types by number and location of masts. The six designations are sloop, cutter, cat, ketch, yawl, and schooner. Although in defining and describing these six rigs I may use terminology associated with the sail plan, the rig type has nothing to do with the number of sails, their arrangement or location.